No Idea: Tristram Shandy, transgressive creativity, John Locke’s tabula rasa, and the legal imaginary

Marett Leiboff

Legal Intersections Research Centre, Faculty of Law University of Wollongong

Abstract

Pray, Sir, in all the reading which you have ever read, did you ever read such a book as Locke’s Essay upon the Human Understanding? ——Don’t answer me rashly, –because many, I know, quote the book, who have not read it,—and many have read it who understand it not:— Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Vol. II, Chap. II

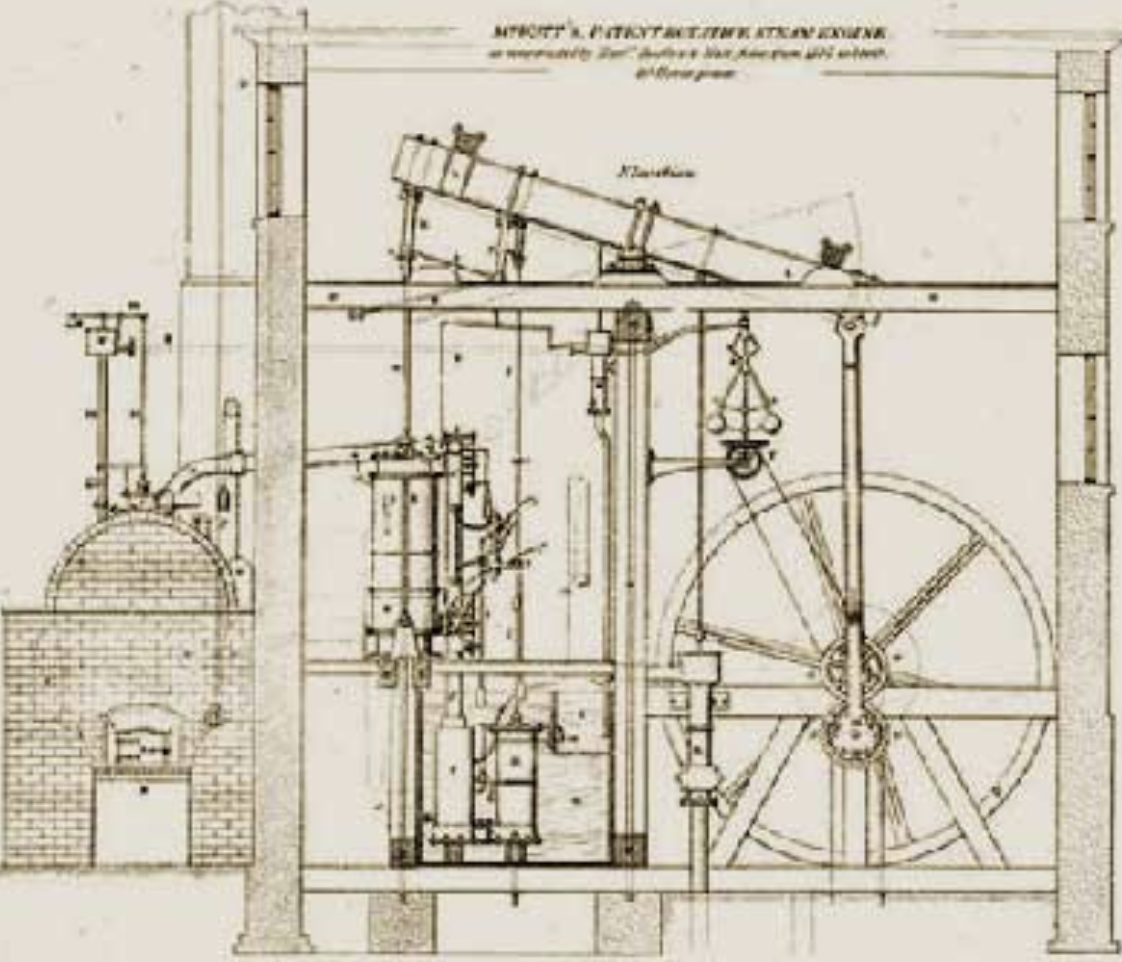

John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, first published in 1690, contains the blueprint for copyright law’s axiomatic distinction between unprotectable ideas and protectable expression. Locke claims that our minds are blank slates – the famed tabula rasa – which draw upon freely available ideas that interact with the mind to create expression. Thus sense data – ideas – must be free and available for all. Only expression, as a production of the output of ideas, can be the subject of copyright protection.

This seemingly simple delineation between idea and expression is an artifice which relies upon a mechanical and imaginary mode of thinking that does not conform to the conditions in which creativity occurs. Yet it is grounded in a long since discredited theory of the mind. While Locke’s notion of idea eventually persuaded the courts during the 18th century literary property debates, thus vouchsafing its place in copyright, its premise was the subject of considerable hilarity even during the same period.

Indeed, Locke’s conception of ‘idea’ was far from accepted during the 18th century. In this paper, I will trace the key concepts underpinning Locke’s conception of idea and their dismissal through the agency of Laurence Sterne’s digressive comic masterpiece The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. This nine- volume novel published during the middle of the 18th century not only sent up Locke’s construction of the processes of thought and the notion of idea itself, but through the fabric of its creation – the use of blank and black pages, squiggles and dashes, interspersed sheets of marbled paper – and the textual devices used throughout, Sterne sought to unravel its central tenet: that creation and thought cannot be contained and controlled mechanically and mechanistically. Tristram Shandy’s shambolic proto-21st century creativity provides a critical gesture through which to explore the founding ideals of the 18th century copyright cases.